James Storer - the first African American worker at the Armory, circa 1912

The African American community in Springfield dates back at least to the Revolutionary

War era, but was relatively small until World War II, when many Black workers

came from the South to find jobs in the industrial cities of the north. Springfield

Armory hired these men and women to fill its expanding wartime workforce. After

the war, many were laid off, and of these most left Springfield, the

men mostly to other industrial jobs in the midwest and the women back to their

homes. Some, like Stanley Desmond,

stayed on at the Armory, making careers as machinists.

Revolutionary War era

The conspicuous presence of African-Americans within the local community was

noted as early as the Revolutionary War in the diaries and letters of the German

soldiers (defeated at Saratoga by the Continental Army) marched onto the grounds

of the newly-established Springfield Arsenal in the Autumn of 1777 (where the

Springfield Armory NHS and Springfield Technical Community College are today).

The presence of African American soldiers was also noted in the ranks of almost

every regiment of Washington’s Continental Army even as enslavement continued

to hold many in servitude. The end of the war in 1782 brought, however, an end

to racial servile enslavement in Massachusetts. Thereafter, African Americans,

never numerous in Massachusetts before that time, became an even smaller minority

until a few decades prior to the Civil War. It was during that bloody conflict

that the Massachusetts 54th Regiment, some of whom came from the local community,

forever removed any doubt about the depth of their commitment to liberty.

Nineteenth Century

The small population of African-Americans in Springfield during the mid-1800’s

included a prominent man named Primus Mason who traded in leather and hides with

the armory. Mason Square in Springfield is named for him. This was also a time

in Springfield that witnessed the turning of the African American congregation

of St. John’s

Church to the plight of those enslaved elsewhere in the United States by virtue

of their color. These were years when John Brown lived for a while in Springfield

(himself a member of St. John’s congregation and where his Bible rests

to this day), Frederick Douglass walked with us, and many more who would soon

shed their blood on southern battlefields.

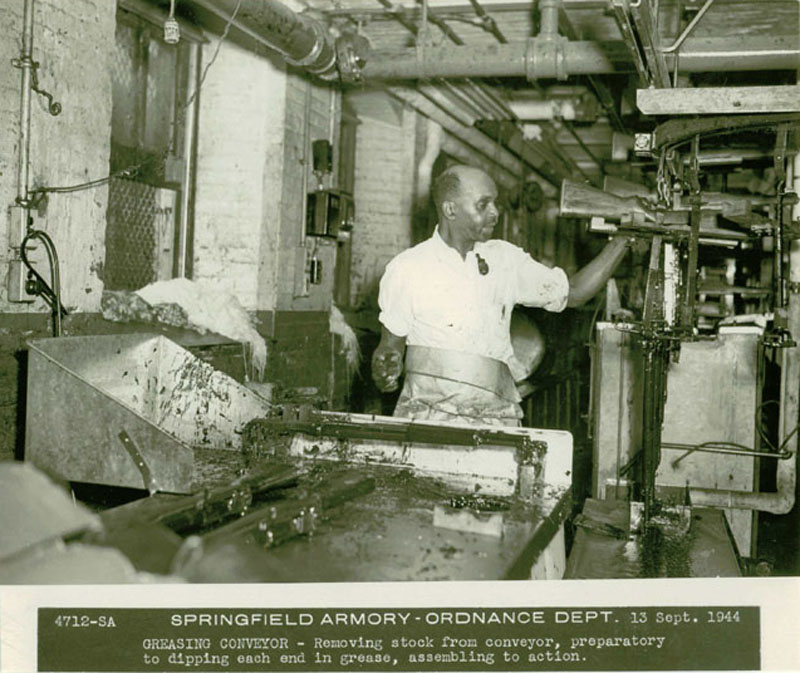

A worker on the greasing conveyer, removing stocks to get

ready for assembling to action.

Twentieth Century

Joseph William

Bowers, in his 1914 Graduation thesis The

Springfield Negro cites the African American population of Springfield

at 1841 people. He then breaks this number down by state of origin, length of

residency etc. He gives numbers employed in various occupations, and union membership

information, property ownership, schools, churches, and civic organizations attended.

Emmett J. Scott's classic study, Negro

Migration During the War, presents data relating to the causes and consequences

of migration from South to North during World War I.

Church organizations were vital to the community, especially those provided

by St. John's Congregational Church. Under the direction of the Rev. Dr. William

N. DeBerry, St. John's incorporated an agency to support its community organizations. St.

John's Institutional Activities is a pamphlet published in 1921 and updated

in 1926, describing its social services, including boys' and girls' clubs, choirs,

housing and a summer camp. The camp, now called Camp Atwater, is still in operation

today.

A jolly group of workers eating lunches together

St. John's also carried out research on the Black community and published

three Sociological Surveys, in 1905, 1922 and 1940.

The 1905 survey is not available, but is referenced in the Bowers thesis

of 1914. Together they provide interesting comparative data and analysis of the

community from the pre-WWI era through the Depression.

The Springfield Daily News November 15 1943 reports on continuing racial discrimination in hiring, relative equality of treatment at the Armory, and attitudes of Springfield whites and blacks in general.

In 1930, St. John's Institutional Activities separated from St. John's Church

and changed its name to The Dunbar Community League. Rev. DeBerry remained the

leader of the new organization, which published the Dunbar

Record, an annual report. The issues collected here cover the WWII years,

1941 - 1945.

|