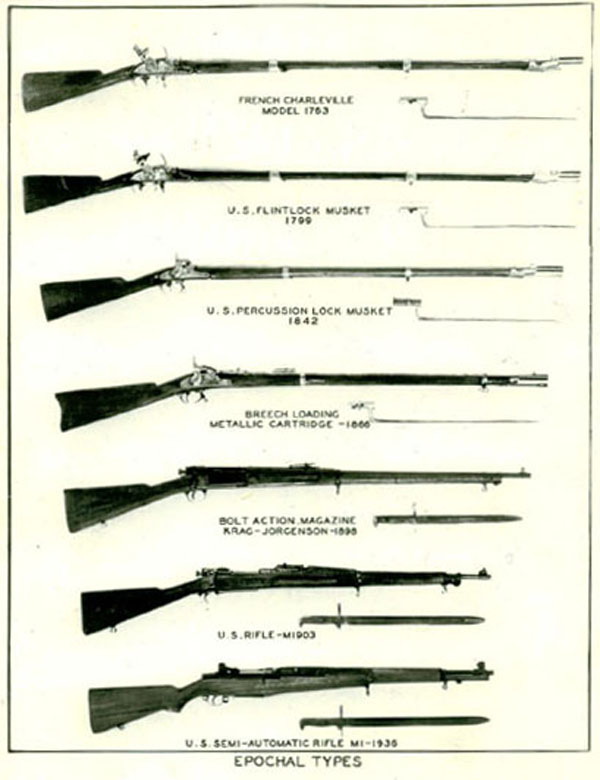

Different models of rifles through history, from 1763-1936

The government-issue weapon to a soldier of the line at the time of the country’s

centennial carried the same name as the weapon that helped win the Civil War

just over ten years earlier: the Springfield. Yet, the Springfield of 1876 wasn’t

the same as the Springfield of 1863. New design innovations from both the Springfield

Armory as well as older private sector designs combined to streamline the physical

movements involved in reloading a rifle. As a result, the rate at which a soldier

could fire was greatly improved. However, tight governmental budgets

prevented the full development of these improvements. Ironically, the industrial

processes and techniques that had been pioneered by the Springfield Armory before

and during the Civil War were now being advanced by private industry, even as

the Armory itself was hobbled by governmental inertia and parsimony.

Just over 16 years later, the blow of the defeat at Little Bighorn was still

palpable to many in the United States Department of Ordnance and its main center

of innovation and manufacturing, the Springfield Armory. Custer’s 7th Cavalry,

regardless of doubts about the competency of its commander, was clearly outnumbered,

and, more significantly, outgunned. A preponderance of privately manufactured,

and technologically superior weapons in the hands of Lakota, Arapaho, and Northern

Cheyenne warriors especially contributed to the last overwhelming Native American

victory over the United States Army and its government-issue Springfield.

During the years following Little Bighorn, civilian engineers and military

officers at the Springfield Armory identified two major problems that needed

to be solved with the issuance of a new rifle. First was the primary dilemma

of arms manufacture: rate of fire vs. waste of ammunition. Where was

the balance? Clearly, Little Bighorn proved that the current version of the Springfield

wasn’t good enough. Second, advances in chemistry produced smokeless powder,

which could both prevent the enemy from spotting the source of a bullet, and

also increase the speed of the projectile. But this increased speed also increased

the strain on the working parts of the rifle, which essentially dictated the

adoption of a completely new rifle. For the second time in its history, just

as it did when it produced its very first musket, the Springfield Armory went

outside its walls - to Europe - for its next major firearm.

|