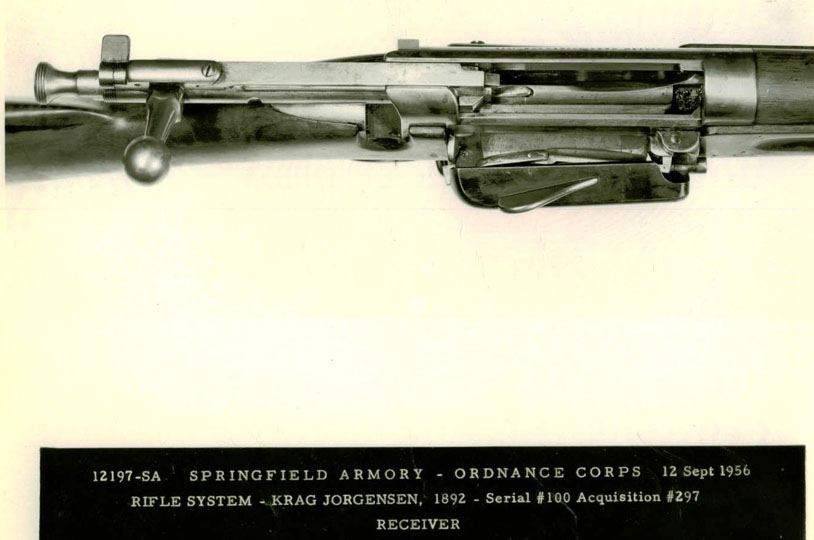

The Receiver of the Krag-Jorgenson Rifle

The progression of small arm design prior to 1892 was more of an evolution than separate institutions of various models. Each successive generation carried an improvement, sometimes slight and occasionally major, over the previous model, making most models technically different, but closely related. That stopped with the introduction of a completely new Norwegian design in the Krag-Jorgensen.

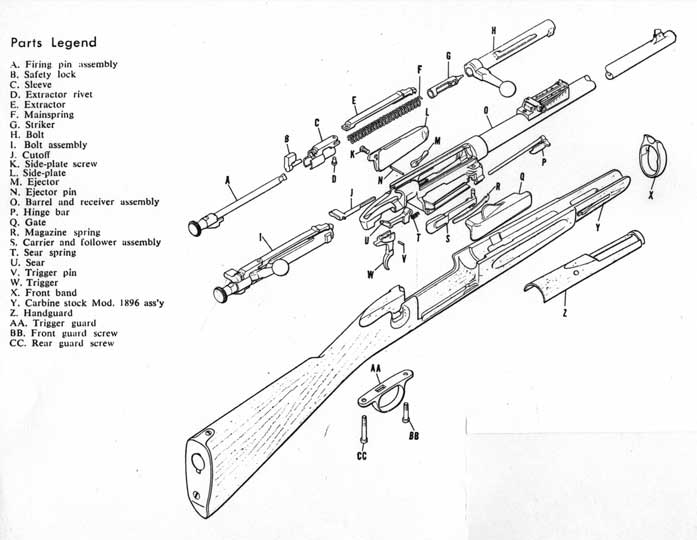

This presented an enormous problem to the Armory. The previous model, the Springfield Trapdoor, was composed of about fifty parts, and the new Krag with its new and more complicated mechanisms had 99 separate parts. It’s one thing to make fifty parts interchangeable, especially when the Armory has been making interchangeable parts to related models for most of the 19th Century. It’s quite another thing to make 99 completely unfamiliar parts interchangeable. The machinists at the Armory were more than up to the task.

An Exploded View of the Krag-Jorgenson Rifle

A radical change in design requires a radical shift in manufacturing operations.

Financial restraints precluded complete replacement of all the machinery at the

Armory. But still, all the machinery was analyzed in terms of the mechanical

operations required to make the new Krag design and simultaneously achieve interchangeability.

As a result, some machinery was clearly obsolete and was replaced outright with

new machines, and some worked perfectly fine and stayed. For example, the mechanism

to rust-proof barrels en-masse during Civil War was the same to rust-proof barrels

of the Krag. However, some machines changed in function but not in form and still

some changed slightly in form but not in function. It was in these “little kinks and devices” created to modify existing machinery to do different work that highlight Armory workers’ continuing technical ingenuity and creativity.

Colonel Alfred Mordecai, Commandant of the Springfield Armory during the Krag years, made it a priority to modernize machinists’ operations in conjunction with updating the machinery. Under pressure from his bosses at the Ordnance Department to quickly produce this new rifle, he made an effort to replace time-consuming hand-work – the remnants of the old method of crafting a firearm – with efficient specialized machine operations. He did this with some success, but certain finishing and filing work wasn’t able to be replicated by a generic machine operation at that time, and several hand tools remained on the shop floor. Many of these hand operations were common at the Armory up to the early years of World War II, when “better” technology eliminated almost all hand work.

|