The AFGE fought for the rights of Armory workers during WWII

Well into World War II, several disputes between workers and management arose

at the Armory in which the American Federation of Government Employees (AFGE)

Lodge 431 played a part. The union believed that, in issuing orders to civilians,

the uniformed officers at the Armory were overstepping the boundaries set by

Civil Service rules. The union itself, however, was not universally acknowledged

as the civilians' representative in negotiations with management. The longer-employed

supervisors, who were organized as the "20-year

Club," tended to prefer relying on Congressional and Civil Service protection,

and to put more faith in getting amendments passed to laws affecting all government

plants. The managers looked askance at the AFGE, whose meetings in 1944 drew

attendance of about 200 but which claimed 5000 paid-up members. It evaded submitting

a roster of membership, while the other smaller union, the National Federation

of Federal Employees local, did so, showing a membership of about 145. Management

felt that any union should play an advisory role only, since legislation and

Civil Service rules left so little scope to the Armory itself for determining

its own conditions.

After proposing formation of a Labor-Management Committee in March, 1944,

the AFGE subsequently rejected it when the management insisted on including representatives

from the other union, AFFE, and the 20-years Club, and would not give AFGE more

weight on the committee. This left them to rely on direct representations to

the commanding officer, and on newspaper publicity. The issues at stake were

management fairness in requesting draft deferments for individual Armory men,

and how much weight to give seniority in making inter-department transfers and

promotions. The Works Manager, Lt. Col. Huth, was accused of favoritism in promoting

a certain foreman of lesser seniority to civilian head of Manufacturing Inspection.

The AFGE went to Washington to appeal to the Chief of Ordnance, who upheld Huth's

decision.

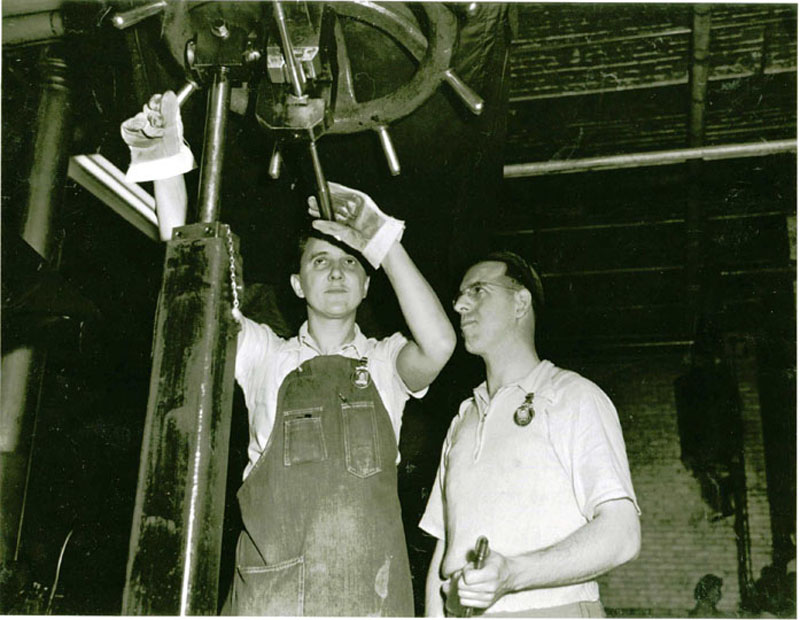

A barrel straightener is inspected as she does her job

Despite having lost face in this fight, the AFGE leaders took on the task

in mid-summer 1944 of representing the rod-straighteners who had (illegally)

gone on strike for six days to protest a cut in the piece rate for straightening

rods, mentioned above. They wanted their work records cleared of bad marks due

to their strike, but the commanding officer refused to do so, and the Chief of

Ordnance also rejected their appeals. The AFGE then broadened the attack through

the press by charging waste and mismanagement at the Armory, and threatening

to carry the campaign to the House Committee for Military Affairs unless the

Ordnance Department investigated the situation. An investigation by the

Ordnance Department ensued, even though the AFGE attempted to retract its demand

for one, but the investigation did not support the charges.

In the course of this dispute the commanding officer died and was replaced,

but the new one also ran afoul of the AFGE late in 1944 in his handling of a

request by 46 foremen for clarification of their status relative to the officers

assigned to their shops. The AFGE then in time-honored manner called on Massachusetts

Congressmen and Senators for a non-military investigation of the Armory, charging

that the dual military-civilian management of the shops was intrinsically wasteful

and that veto of the civilian foremen by their uninformed officer counterparts

was dictatorial. The AFGE called for civilian supervision of the Armory, retaining

officers only for product inspection. Their campaign for an investigation ran

on into 1945. It was espoused by Massachusetts Senator Walsh, but with little

result beyond the three-day suspension of the AFGE president for spreading

false statements after he equated the authority of "schoolboy" officers

over skilled craftsmen with fascism. The war's imminent end suspended the union's

campaign for demilitarizing Armory management. About half of the 9,000 men

and women in the wartime work force were laid off after V-E Day in the spring

of 1945; the AFGE president himself resigned and ran for [Springfield] city council.

The AFGE labor disputes were the last in Armory history and appear to have

been a side-effect of unusually large and rapid growth of the Armory labor force,

military as well as civilian. By the time the AFGE disputes began, virtually

all Armory officers were from the reserves, as wartime demands swept up regular

Ordnance Department officers for other assignments. Thus the disputes grew

from friction between parties with little if any Armory experience. During most

periods, management reliance on the skills and experience of workers--critical

elements in achieving Armory standards of interchangeability--tended to minimize

potential conflict.

|